Francis Acton was born on 20 October 1830 in Birmingham, Warwickshire, England. He was the son of Thomas Acton, a brickmaker, and his wife Sarah (née Harper Newman). The Acton family had roots in Staffordshire – Thomas and Sarah married in 1807 in Abbots Bromley, Staffordshire, and by the 1830s they relocated to the industrial city of Birmingham. Francis was baptized in Birmingham in 1831, and he grew up with several siblings, including a younger brother, John Acton (born March 1833). Baptismal and census records indicate that both Francis and John spent part of their childhood in the cathedral city of Lichfield, Staffordshire (the family’s original home area), even though they had been born in Birmingham. This suggests the Actons returned to Lichfield by 1841, likely after Thomas’s death in 1840. Notably, John Acton did not follow Francis to Australia; John remained in England and became a builder in Victorian London. The shared parentage (Thomas Acton and Sarah Harper Newman) documented on John’s baptism record at St. Martin’s Church in Birmingham confirms that John and Francis were brothers. This genealogical context firmly links Francis Acton of Queensland to the Acton family of Birmingham/Lichfield, and explains his origins before emigration.

Emigration to Queensland (1862)

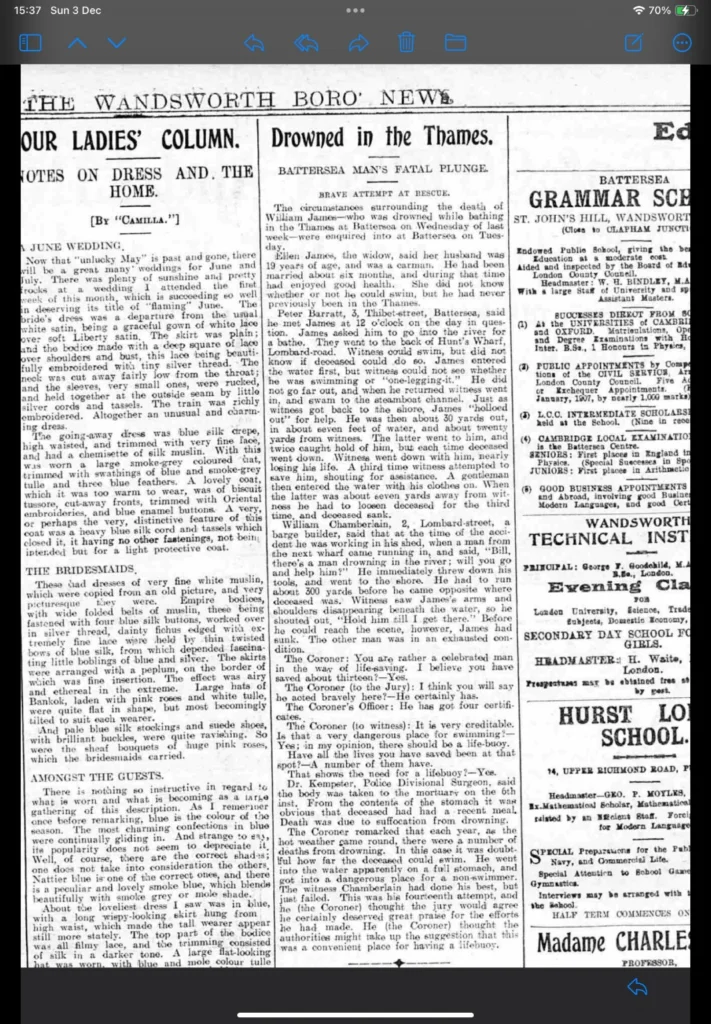

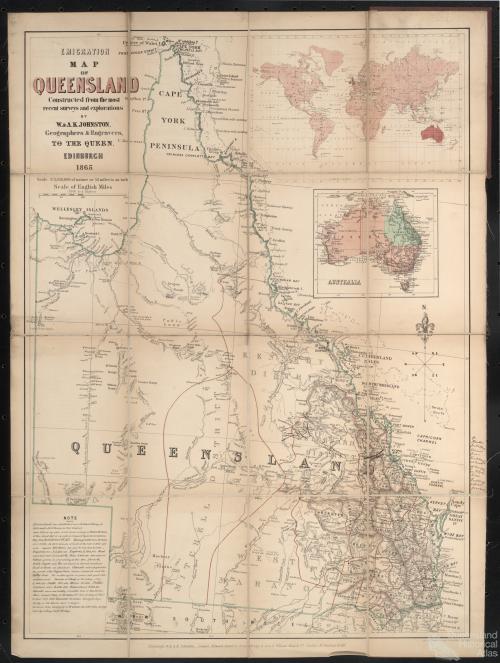

In the mid-19th century, Queensland was eager to attract British immigrants. Queensland became a separate colony in 1859 and, over the 1860s, its government offered assisted passages and land incentives to eligible migrants. Enthusiastic agents in Britain promoted Queensland as an ideal destination, distributing brochures and even maps highlighting the journey and opportunities. One such promotional item was the 1865 “Emigration Map of Queensland”, produced in Edinburgh, which illustrated the sea voyage route from the British Isles to Queensland and described the young colony’s climate and resources. The typical passage was by sailing ship, taking roughly 3 months and spanning ~17,500 miles via the Cape of Good Hope and Bass Strait. Many Britons heeded the call – in 1862 alone, over 8,500 British immigrants arrived in Queensland, swelling the colony’s population.

Francis Acton was among these 19th-century English emigrants. On 1 July 1862, in England, Francis married Elizabeth Brockwell, a young woman originally from Middlesex (England). Shortly after their wedding, the couple embarked for Australia. According to family accounts, Francis and Elizabeth Acton set sail in 1862 under an assisted passage scheme, arriving in Queensland later that same year. Shipping and immigration records from his voyage note Francis’s origins as “Lichfield, Staffordshire” and list his father as Thomas Acton (occupation given as farm labourer) – details he likely provided to authorities upon immigration. These records, while slightly mis-stating his exact birthplace, corroborate his identity and family background. By undertaking the journey, Francis and his bride joined the wave of hopeful settlers drawn by Queensland’s promises of land and prosperity.

Life in Queensland: Goldfields and Family

Initially, the Actons tried their luck in the Queensland goldfields. In the early 1860s, gold had been discovered in several parts of the colony, and a major rush would soon ignite in the north. Family recollections suggest that upon arrival, Francis and Elizabeth traveled to Charters Towers in northern Queensland, where Francis worked for a time in the gold mines. (Charters Towers’ goldfield was discovered at the end of 1871 and boomed in the 1870s, earning the town the nickname “The World” for its richness and population.) Life as a gold miner was rugged and speculative – miners toiled in hot, remote diggings hoping to strike it rich. It’s not clear how long Francis stayed on the goldfields or how successful he was, but this experience was a common chapter for many new arrivals in Queensland during the gold rush era.

Miners at work in the Charters Towers gold diggings, c.1878. Gold mining boomed in Queensland in the 1870s, and Francis Acton reportedly spent some time working in the Charters Towers mines. Like many immigrant men, he may have labored in harsh conditions with simple equipment, hoping to improve his family’s lot.

By the mid-1860s, Francis and Elizabeth Acton had settled in Brisbane, the colony’s capital. In fact, as early as 1864–1865 the Actons were living in the inner-city suburb of Fortitude Valley, Brisbane. Francis’s occupation in Brisbane isn’t recorded in surviving documents, but given his background as a brickmaker’s son and his stint as a gold miner, he may have worked as a laborer or tradesman in the growing city. There is also anecdotal evidence that the Actons ran a store in the Brisbane district of Lutwyche in the late 1870s–1880s (a store later remembered by descendants) – indicating Francis might have become a small business proprietor as his family grew.

One of the richest aspects of Francis Acton’s life in Queensland was his family. He and Elizabeth had a remarkably large family: by the 1870s and early 1880s, they became parents to approximately 12 children (at least 7 sons and 5 daughters). Their children were all born in Queensland – true first-generation Australians. The Acton children’s birth records show the family residing in the Brisbane area during these years. For example, a daughter, Emma Jane Acton, was born in September 1865 in Fortitude Valley, and a son, Francis Herbert Acton, was born in March 1863 with a Brisbane registration. The brood included: Francis Herbert Jr. (b. 1863), William Henry (b. 1864), Emma Jane (1865 – this first Emma died in infancy), Ellen Elizabeth (b. 1866), a second Emma Jane (b. 1869), John Walter (b. 1870), James Edgar (b. 1872), Charles Henry (b. 1874), Edward “Leguire” Acton (b. 1876), William Thomas (b. 1878), Ada Maud (b. 1882), and Lillian Frances (b. 1883). (It was not uncommon in that era to reuse names of deceased children; the Actons, for instance, named a later daughter Emma Jane in 1869 after losing their first baby of that name in 1865.)

Tragically, several of Francis and Elizabeth’s children did not survive to adulthood – a fate all too common in the 19th century. Their first son, William Henry, died as an infant in 1865. In 1883, their 12-year-old son John Walter Acton died, just months before Francis himself (father and son died in the same year). Another son, William Thomas, lived into young adulthood but passed away at 22 in 1900. Daughter Ada Maud died at age 11. Despite these losses, many of the Acton children survived and went on to marry and establish lines of their own in Australia. For instance, James Edgar Acton (born 1872) lived to 84 and raised a family in Brisbane, and Francis Herbert Acton Jr. (born 1863) became a farmer in Queensland and lived into 1920. Through these children, Francis and Elizabeth’s legacy continued in Queensland for generations.

Later Years, Death and Legacy

By the early 1880s, Francis Acton was a long-established resident of Brisbane, known as a family man with deep roots in the community. After two decades in Queensland, he had witnessed the colony’s rapid growth – from the rough frontier of the 1860s gold rush to a more settled society in the 1880s. In 1882, Elizabeth became pregnant with their final child. However, Francis would not live to raise this youngest daughter.

Francis Acton died on 19 September 1883 in Brisbane at the age of 52. (His age was sometimes misreported – one cemetery record lists him as 58, but contemporary sources and his baptism suggest 52–53 is correct.) Just five weeks after his death, Elizabeth gave birth to their last baby, Lillian, on 28 October 1883. One can only imagine the mixed sorrow and joy for the Acton family at that time: mourning Francis’s passing while welcoming a newborn. Francis was buried at Lutwyche Cemetery in Brisbane on 20 September 1883. His gravesite (in the Anglican section of Lutwyche Cemetery) is the final resting place for him and later many of his family. The headstone inscription (now recorded in cemetery indexes) names him as the husband of Elizabeth and, interestingly, lists his father as “John” – likely a mistake on the part of whoever ordered the inscription, since we know his father was Thomas Acton. Elizabeth Brockwell Acton, Francis’s widow, survived him by almost 19 years; she passed away in 1902 at age 59 and was buried in the same cemetery, presumably alongside Francis.

At the time of his death, Francis’s estate was modest. Probate was granted to Elizabeth Acton, and his personal assets were valued at around £200 – a non-trivial sum for a working-class man of that era, but not a large fortune. This suggests that while he may not have struck gold riches or amassed great wealth, he was able to provide a stable life for his family in the colonies. Indeed, the real legacy of Francis Acton lies in the family he raised and the new roots he planted in Australian soil. His children and their descendants became farmers, soldiers, businesspeople, and community members in Queensland and beyond, helping build the young nation. For example, his son James Edgar Acton served in World War I (honored on a local school memorial in Windsor, Brisbane), and many of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren continued to live in Queensland throughout the 20th century.

From a genealogical perspective, Francis Acton’s story also offers a contrast with that of his brother. John Acton, the younger brother back in England, lived out his days in London’s expanding suburbs (working as a master builder) and died in the early 1900s. The two brothers – one who stayed in the Old World and one who ventured to the New – illustrate the diverging paths British siblings could take in the Victorian era. Francis’s emigration to Queensland was part of a larger historical movement of English families to Australia in the 19th century. His successful establishment of a family line in Queensland confirms the familial tie that was suspected: Francis was indeed the brother of John, and both were sons of Thomas and Sarah Acton. That connection, once only a theory based on names and dates, is now backed by multiple records spanning two continents.

In summary, Francis Acton emerged from humble beginnings in Birmingham/Staffordshire and made a life for himself in colonial Queensland as a miner, family man, and ultimately a patriarch of an Australian branch of the Acton family. He married an English wife, started a large family, and contributed to the growth of Brisbane during its formative years. He experienced the hardships of pioneer life – from gold rush booms and busts to personal loss – but also the rewards, living to see his older children grown and settled. His death in 1883 cut his story somewhat short, but the timing meant that he had spent just over 20 years in Queensland – enough time to firmly establish the Acton name there. Francis Acton’s journey from the brick yards of Birmingham to the gold fields of Queensland and finally to a quiet Brisbane gravesite encapsulates the 19th-century migrant experience. It also provides rich context for his family’s genealogy, confirming his place as the link between an English past and an Australian future.

References:

Birth, marriage, and baptism records from Birmingham and Lichfield (cited above)

Queensland immigration and civil registration indexes (births, deaths, marriages)

Cemetery records (Lutwyche Cemetery, Brisbane)

Family recollections and compiled genealogies

Historical context sources on 19th-century English emigration to Queensland, including contemporary promotional materials and immigration statistics.